Deforestation is a major environmental issue in South America’s Atlantic Forest region. Compared to deforestation in the Amazon Basin, this ecologically-significant region receives significantly less attention. In Misiones Province (containing Argentina’s share of the Atlantic Forest), increasing agricultural exploitation for the production of yerba mate (one of the province’s primary agricultural activities) has altered the landscape. This project has two primary goals. The first is mapping the geographies of yerba mate production in Misiones in recent years. The second is to assess if increasing yerba mate cultivation appears to be related to recent forest loss in the province.

Historical & Environmental Contexts

Misiones contains the largest remaining continuous areas of the Atlantic Forest and, in recent decades, has seen its cover of primary forest significantly erode (Izquierdo et al., 2008; Izquierdo & Clark, 2011). The province's native forest vegetation varies subtly due differences in climate and relief, but most is characterized as a dense agglomeration of large trees (often anchored by Aruaucaria angustifolia), ferns, epiphytes & lianas. (Eidt, 1971). The region’s remaining forest cover provides habitat for highly biodiverse ecosystems that exhibit high rates of endemism (Costa et al., 2000; Vale et al., 2018; Werneck et al., 2011). Some species facing significant risk of habitat loss include the giant anteater, jaguar, jacare caiman, and numerous species of birds, insects, and trees (Costa et al., 2000; Hanisch et al., 2015; Vale et al., 2018; Werneck et al., 2011). The elimination of habitat presents a direct threat to this biodiversity and the ecosystem services that it undergirds.

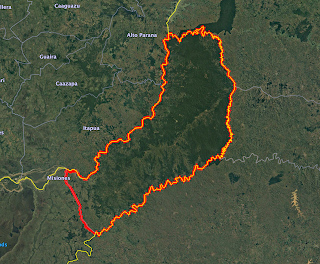

Historical land-cover imagery of the province, generated through Google Earth, is seen below in Figure #1. While the fact that Misiones contains the lion's share of the region's remaining forests, the historical imagery may be a bit deceiving at first glance. This is because Misiones has a large timber industry for which monocultures of exotic Pinus & Eucalyptus replace stands of the province's remaining primary forest. This project originally sought to include closer examination of the province's growing forestry industry, but, due to lackluster data availability and accessibility, this beckons attention in future research projects.

Figure #1: Historical Imagery Series of Land-Cover in Misiones (Google Earth, 2020)

1990

2005

2020

Misiones, at 29,801 km2, is Argentina’s third smallest province and makes up just over one percent of the country’s total area. While relatively small, this province accounts for roughly 90% of the country’s production of yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) (Rau, 2009, 51). Yerba mate is a perennial tree crop whose leaves are harvested, dried, ground up, and then widely-consumed daily across Argentine society as a symbol of national identity, appropriating Indigenous Guaraní customs as their own. An photograph of a sculpture from the streetscape of Posadas (the provincial capital) is seen in Figure #2 below.

Figure #2: Public art depicting yerba mate preparation in Posadas, the provincial capital. (Photograph by author, 2018)

Yerba mate, once mainly harvested from wild stands, is now mostly produced through commercial plantation agriculture (Dohrenwend, 2019). Most typically, the cultivation process in Argentina goes as follows. First, producers purchase saplings of roughly one year of age, dubbed "plantitas." After three to four years, the young tree is ready to be harvested for the first time. This process continues over the tree's lifespan at various producer-determined intervals, generally from April to September (autumn and winter). The most common intervals are 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months. Once harvested (most often by seasonal migrant laborers), large bales of branches, covered with leaves, are transported in the beds of overflowing trucks to nearby drying facilities. Here, direct fire is briefly applied to the leaves by a mechanized system and then they are ground up, aged, and packaged. The aging process contrasts Argentine production with Brazilian production, as Argentine yerba mate tends to be much darker in color that its unaged counterpart (Dohrenwend, 2019).

Long inhabitated and managed by Tupi-Guaraní peoples, significant environmental change at humanity's direction has occured in the Atlantic Forest over the last 2-2.5 thousand years (Iriarte et al., 2017). During the colonial period (up to their explusion in 1767), much of the region was under the influence of the Jesuits. This was especially the case in Misiones, named for the 30 Jesuit missions in the area (Dohrenwend, 2019). The Jesuit period saw the exploitation of Guaraní indigenous knowledge in the emergence of formal yerba mate cultivation on the missions (Nimmo & Nogueiro, 2019). After explusion and eventual independence, the borderlands area straddling Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay saw political instability culminating in the War of the Triple Alliance. As a result of the war, Paraguay ceded significant territory that had been claimed by Argentina and Brazil. With overwhelming internal demand for yerba mate, but no political sovereignty over any area within its growing range, the Argentines had been especially eager to gain firm control over their territorial claims (Dohrenwend, 2019).

After the war, the vast majority of Misiones was auctioned off and two million hectares were divided between 29 investors (Sawers, 2000, 21). The average tract size was 70,000 hectares, with one investor granted 600,000 hectares (Sawers, 2000, 21). Characterized as largely absentee landowners, the Argentine government sought to settle the region as a means of cementing territorial sovereignty (Nodari, 2018). The national government began active promotion of settlement efforts in the region in the early 20th century through land reform (Sawers, 1996). Often settlement efforts were operated by private settlement companies, establishing an assortment of colonies that attracted European settlers entering the continent through São Paulo. This stands in stark contrast with most other European settlement in the country which entered through Buenos Aires (Eidt, 1971; Nodari, 2018). The recruitment of recent European immigrants through Brazil was necessary as few porteños were interested in moving northwards to the selva misionera (Eidt, 1971). The Pampas vast and fertile grasslands offered highly-productive land for conventional export agricultural commodities (like wheat) demanded by the distant and emerging Global North economies and their growing fleets of industrial workers (Scobie, 1964).

Many individual colonies clustered along waterways in the territory's southwesern half and tended to be ethnically-homogenous, representing settlement by Germans, Polish, Ukrainians, French, and Swedes (Bartolomé, 2004; Eidt 1971). Around the time of yerba mate's return to cultivation (after significant government research investment), the major condition for the land grant was that farmers had to deforest a portion of their land for yerba mate production. In addition to yerba mate and subsistence crops, large swaths of forest were cut down for timber, some lumber was used for local construction, while much was transported downriver for use in a spine of growing interior cities running south to the Río de la Plata's mouth (Eidt, 1971).The result of this wave of settlement was significant loss of native forests across most of the territory's flatter southwestern half. In addition to encouraging settlement, the national government also asserted their sovereignity in the area through the designation of protected areas, mostly in the sparsely-populated and hillier northeastern half (like that at Iguazú Falls) (Freitas, 2018). This strategy by the national government was practiced in other borderland areas of Argentina for similar reasons (Aagesen, 2000). Since 1915, the population of Misiones has increased over 20-fold — from 50,000 to over 1.1 million (Eidt, 1971, 191; INDEC, 2010). Though representing a small share of Argentina's total population, the population density of Misiones is more than double that of the country (37/km2 vs. 14.4/km2) (INDEC, 2010).

The last several decades in the region have been characterized by significant internal migration from rural areas to the the province's main cities: especially Posadas, Oberá, and more recently, Puerto Iguazú (Izquierdo et al., 2008). As a result, many areas formerly under subsistence practices have gradually transitioned back towards forestlands (Izquierdo et al., 2008). At the same time, the previously-mentioned re-emergence of the forestry industry has gobbled up much of this land, hindering the region's ecological regeneration with the national governments encouragement (Izquierdo et al., 2008; Izquierdo & Clark, 2012).

Production Maps & Discussion

Figures #3-6 below help us examine the impacts of expanding yerba mate cultivation on subtropical deforestation. Each interactive map features a set of layers that can be toggled on and off by the user, including a layer depicting the provincial boundaries. Data sources for these maps include production statistics from the Instituto Nacional de la Yerba Mate (INYM, 2012; 2016; 2020a; 2020b) and tree-cover loss figures from the World Resources Institute's Global Forest Watch (World Resources Institute, 2020). National agricultural censuses and provincial statistical abstracts provide limited utility, because of the project's focus and scale. Their irregular and inconsistent nature further limits their utility to the project. I hope to be able to find higher quality archival records in the future when I am able visit Misiones next.

INYM publishes irregular & relatively-limited data on the evolving amounts of cultivated area dedicated to yerba mate in hectares. While long stable, the amount of cultivated area has steadily crept up in recent years (Dohrenwend, 2019; INYM, 2016; INYM, 2020b). INYM also provides regular, yearly production data (in kilograms), back to 2011 and on a regional scale (INYM 2012; 2020a. These numbers have also steadily increased over the last decade (INYM, 2012; 2016; 2020). I utilize INYM's regional classification categories for the province's 17 departments including: Central (Caínguas, 25 de Mayo, Oberá, Leandro N. Alem, & San Javier), Northwest (Iguazú, Eldorado, & Montecarlo), Northeast (Gral. Manuel Belgrano, San Pedro, & Guaraní), West (Lib. Gral. San Martín, & San Ignacio), and South (Capital, Candelaria, Apóstoles, & Concepción). I depict the regional production data in its original classifications (Figure #5), while I depict the departmental cultivated area data at both the departmental scale (Figure #3) and the regional scale (Figure #4). Though the embedded maps appear small on the blog, clicking on the icons in the upper-left corners provides a better view in another tab.

Figure #3: Yerba Mate Cultivated Area by Department

Figure #3 (seen above) shows several layers of data (INYM, 2016; 2020). The first layer (shown in the default view) shows cultivated area in 2020 dedicated to yerba mate in graduated shades of green. The second layer shows the percent increase in hectares from 2016 to 2020. The province as a whole saw its cultivated area dedicated to yerba mate increase 5.9% between their 2016 and 2020 reports. This represents an increase of 8,537 hectares — from 144,118 hectares to 152,655 hectares.

Figure #4: Yerba Mate Cultivated Area by Region

The largest percentage increases were seen in Candelaria and San Pedro. Candelaria, among the smallest departments, has the least cultivated area dedicated to yerba mate of all departments (just 16% of the next smallest producer: neighboring, densely-populated Capital). Interestingly, its total increase of just over 100 hectares is among the smallest of all departments. San Pedro, multiple times larger by area than Candelaria, experienced an 18% increase. While producing a significant amount of yerba mate, its large size means yerba mate cultivation takes up a relatively-small percentage of its total land area in comparison with most other departments — just 2.8% in 2020. The third layer show these figures in 2020 in graduated shades of purple. All layers are shown at the regional scale in Figure #4 above.

Most of the departments that experienced the smallest percentage increases are those in the Central and Southern Regions. Long the center of yerba mate production and now geographically-constrained, some of these departments (including Oberá, Caínguas and Apóstoles) already dedicate 10-15% of their total land areas to the decades-old yerbales. These three departments include roughly one-third of Misiones' cultivated area dedicated to yerba mate while producing more than half the provinces' total hoja verde. In the Central region, rapid increased production in kilos (+27% since 2011, as seen in Figure #5 below) is driven by both further intensified production in the legacy producing departments of Oberá and Caínguas (by replacing old, traditional plots with new, high-density plots) and the expansion of cultivated area in nearby 25 de Mayo and Leandro N. Alem. The Southern region shows a similar pattern: with Apóstoles leading the pack in total produced, but modestly lagging behind its regional counterparts in percentage growth in cultivated area (along with neighboring Capital). Production of hoja verde in this region rose 41.7% between 2011 and 2019.

Aagesen, D.L. 2000. “Rights to Land and Resources in Argentina's Alerces National Park.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 19, no. 4:547-569.

Bartolomé, M.A. 2004. “Los Pobladores del “Desierto”: Genocidio, Etnocidio y Etnogénesis en la Argentina.” Les Cashiers Amérique Latine Histoire et Mémoire, 10.

Costa, L.P, Y.L.R. Leite, G.A.B. da Fonseca, & M.T. da Fonseca. 2000. “Biogeography of South American Forest Mammals: Endemism and Diversity in the Atlantic Forest.” Biotropica 32, no. 4b:872-881.

Eidt, R. 1971. Pioneer Settlement in Northeast Argentina. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Freitas, F. 2018. "Argentinizing the Border: Conservation and Colonization in the Iguazú National Park, 1890s-1950s." In Big Water: The Making of the Borderlands between Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay, edited by J. Blanc & F. Freitas. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Google Earth, 2020. "Historical Imagery Series of Land-Cover in Misiones." Google Earth, accessed November 15, 2020.

INDEC 2010. "El Censo Nacional de Población de 2010." Buenos Aires: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos.

INYM. 2012. "Anuario 2011." Posadas: Instituto Nacional de la Yerba Mate.

INYM. 2016. "Superficie Cultivada Por Departamentos, 2016." Posadas: Instituto Nacional de la Yerba Mate.

INYM. 2020a. "Anuario 2019." Posadas: Instituto Nacional de la Yerba Mate.

INYM. 2020b. "Superficie Cultivada Por Departamentos, 2020." Posadas: Instituto Nacional de la Yerba Mate.

Iriarte, J., R.J. Smith, J.G. de Souza, F.E. Mayle, B.S. Whitney, M.L. Cárdenas, J. Singarayer, J.F. Carson, S. Roy, & P. Valdes. 2017. “Out of Amazonia: Late-Holocene climate change and the Tupi-Guaraní trans-continental expansion.” The Holocene 27, no. 7:967-975.

Izquierdo, A.E. & M.L. Clark. “Spatial analysis of conservation priorities based on ecosystem services in the Atlantic forest region of Misiones, Argentina.” Forests 3, no. 3:764-786.

Izquierdo, A.E., C.D. de Angelo, & T.M. Aide. (2008). “Thirty Years of Human Demography and Land- Use Change in the Atlantic Forest of Misiones, Argentina: an Evaluation of the Forest Transition Model.” Ecology and Society 13, no. 2.

Nimmo, E.R. & J.F. Miró Medieros Nogueira (2019). “Creating hybrid scientific knowledge and practice: the Jesuit and Guaraní cultivation of yerba mate.” Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 44, no. 3:347-367.

Nodari, E.S. 2018. "Crossing Borders: Immigration and Transformation of Landscapes in Misiones Province, Argentina, and Southern Brazil." In Big Water: The Making of the Borderlands between Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay, edited by J. Blanc & F. Freitas. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Sawers, L. 1996. The Other Argentina: The Interior and National Development. New York: Perseus.

———. 2000. "Income Distribution and Environmental Degradation in the Argentine Interior." Latin American Research Review 35, no. 2:3-33.

Scobie, R. 1964. Revolution on the Pampas: A Social History of Argentine Wheat: 1860-1910. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Rau, V. 2009. "La Yerba Mate En Misiones (Argentina). Estructura Y Significados De Una Producción Localizada." Agroalimentaria 15, no. 28:49-58.

Vale, M.M., L. Tourinho, M.L. Lorini, H. Rajão, & M.S.L. Figueiredo. 2018. “Endemic birds of the Atlantic Forest: Traits, Conservation Status, and Patterns of Biodiversity.” Journal of Field Ornithology 89, no. 3:193-206.

Werneck, M.S., M.E.G. Sobral, C.T.V. Rocha, E.C. Landau, & J.R. Stehmann. 2011. “Distribution and Endemism of Angiosperms in the Atlantic Forest.” Natureza & Conservação 9, no. 2:188-193.

World Resources Institute, "Global Forest Watch: Argentina." Global Forest Watch, 2020, https://www.globalforestwatch.org/dashboards/country/ARG/.

Comments

Post a Comment